(from our storymap)

In my capacity as a fellow in our faculty research center, I've been doing a lot of support work for the unexpected shift to learning-at-a-distance. At my uni, very few of us have experience teaching online. The faculty (generally) aren't especially enthusiastic, and there hasn't really been a lot of institutional support. So, I wasn't surprised when most of the questions I was fielding took the form of: "I do X in my class. How can I do X online?" Not surprised because that's the ideological frame distance education has relied upon: an exact homology between offline- and online teaching, with the physical classroom replaced by the discussion board, the lectures by videos. But actual online courses (not our band aid efforts to stitch together something in a few days) are structured very differently than their physical counterparts. The best classes maximize their digital affordances and don’t try to simply "reproduce" face-to-face education.

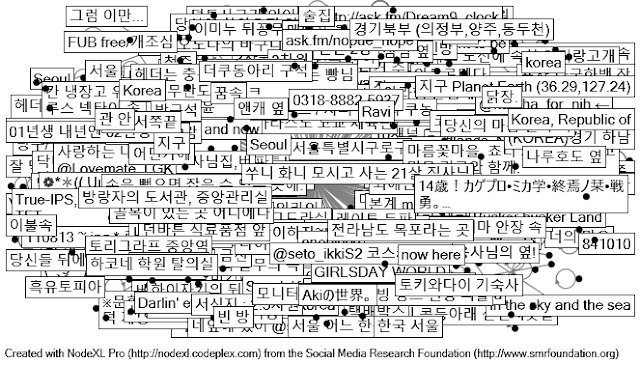

Something similar has happened with ethnography. I have read dozens of semi-panicked posts: if I can't go into the field, perhaps I can go into the digital field? Well - there have been several, thoughtful posts from digital anthropologists on this sentiment, including a recent one in GeekAnthropologist. Reading these, though, I can't help but notice that these would-be digital anthropologists don't really want to be digital at all. And they're not really proposing digital anthropology. If you're studying the lives of people in their (physical) communities, can you really do digital anthropology? In other words, if people are undertaking online/offline lives (whether under quarantine or not), are those lives best understood through digital anthropology? Or are you talking about what my colleague, Matthew Durington, and I have called "networkedanthropology"?

In networked anthropology, we acknowledge the skein of digital and physical connections in people's lives, and we try to recognize and enable the capacities of people to represent those lives through networked, media platforms that make sense to them.

In a quarantined world, what's missing from the social scene? With regards to the production of ethnography, at least one element is missing: the anthropologist. But only that. Even without the anthropologist, social and cultural life continue. And more than that--the documentation and theorization of social and cultural life continues as people record and comment on the things that happen in their lives and in their communities. In this sense, networked anthropology is about capitulation--perhaps we really weren't that important anyway? But we can certainly help people in their own efforts to represent and communicate their identities and communities, and this is, I think, what (at least some) of our colleagues should be doing.

Last summer, we worked on a project in a small neighborhood in Baltimore undergoing rapid gentrification that was leading to the displacement of a long-standing community of African American residents. Collaborating with children at a community center, we helped them (co)produce maps, photographs, video and audio interviews that we put together for an app tour, an exhibit and a performance. It was a great project to work on, and the article that we are submitting on this includes all of them as co-authors. In light of our present pandemic, and in the interest of protecting communities from us, it occurs to me that we (me and Matt Durington) didn't really need to be there at all. Sure - we needed to talk to people and see what they were up to. In the end, though, the images and interviews are produced by people in the community. My point: if we never actually stepped foot in that neighborhood, that would not make it digital anthropology. We would just be doing networked anthropology - anthropology with people who were physically (not virtually) in their communities.

I don't know when the infection rates and death toll of the pandemic will subside. But it seems likely that we will not be able to undertake our in situ research for some time. Even if we can go into the field, it may be in fits and starts, with pandemic flare-ups mandating our social distancing once again. But just because we are not in situ doesn't mean that people in the communities where we work aren’t in situ! By now, we are all used to that peculiar hypocrisy in anthropology that decries colonization and its authorizing gaze, but that still seems to insist on presence in order to undertake anthropology. Perhaps enough of that?