You’ll see them in film, k-dramas, music videos, webtoons and video games: narrow Seoul alleys (골목길), old restaurants with peeling wallpaper, protagonists drowning their sorrows in tent bars (포장마차). Sometimes these images are deployed for critical purpose: e.g., the 반지하 (semi-basement) that the Kim family lives in the 2019 film “Parasite.” And sometimes for nostalgia–with multiple documentaries and websites on the “last urban moon village” (마지막 달동네) of a Korean city. But this is not the Seoul–nor the Republic of Korea (hereafter Korea)--that most people inhabit. Over the last 50 years, urban life in South Korea has been transformed in many ways, with successive waves of state-sponsored gentrification that has culminated with “New Town” developments of block upon block of orderly apartment complexes with mall-like commercial strips between them (Chen et al 2019; Song et al 2019). Here, Korea parallels (and anticipates) urban development elsewhere.

However, this proposed project is not a critique of urban (re)development (재개발), but an inquiry about what remains. Here and there, amidst the gleaming office towers and high-rise apartments of Seoul and other Korean cities, there are older neighborhoods with housing stock from previous decades–small islands of the past. On the one hand, these represent surplus neighborhoods for later redevelopment schemes. On the other, older neighborhoods evoke nostalgia for the past and for what people frequently characterize as a less alienated time. “Moon neighborhoods,” so-called because many were constructed on squats in hills and mountains that were not thought suitable for apartment development, remind people of the struggle and determination of past generations. What happens to these places in the interstices of ubiquitous housing blocks?

If we were doing this research in the United States, the answer would be clear enough: gentrification, abandonment and displacement, the legacy of post-War urban development that may have moved into more hybrid strategies in a neoliberal age, but that still remains devastating to people in working-class communities (Logan and Molotch 1987; Durington and Collins 2019). In South Korean cities, however, “touristifcation” may instead be the result. Rather than move into neighborhoods of older homes without access to infrastructure and amenities, tourists visit instead to snap photos for Instagram posts and to explore (Kim and Holifield 2022). In some cases, the state has facilitated this process by painting colorful murals on neighborhood walls–literally enabling Instagram-able moments. The result is a digital gentrification without the physical displacement of people (Hartmann and Jansson 2024).

My proposed research project is on the way community identity is physically and digitally negotiated in older neighborhoods that have become sites of state intervention, touristifcation and nostalgia. My earlier work in Seoul included places like Ihwa-dong and different neighborhoods along the old city walls (e.g., Bukjeong Maul). These have been the targets of urban regeneration, media representation and tourist development (Nam and Lee 2023; Yun and Kwon 2023). Older housing stock, narrow alleys and colorful murals attract location scouts for k-dramas and film, as well as busloads of domestic and international tourists. But people live in these places as well, people who have little to show for the mediatization and fetishization of their communities. Yet it would not be accurate to conclude that they are powerless against the onslaught of touristification and hallyu media. For one, residents have occasionally risen up against the commodification of their communities, as in the vandalism of artistic murals in Ihwadong in 2016 (Oh 2020). In addition, as one of the most wired nations on Earth, Koreans engage in social media productions across multiple platforms, and document their neighborhoods and their lives in ways that diverge significantly from the Instagram posts and hallyu tours. Finally, communities host events, gallery shows, media broadcasts and other projects that constitute genuine place-making, and stake a claim not only to their homes, but additionally establish what their communities mean (Kim and Son 2017; Kang 2023).

My perspective on these negotiations is one of multimodality, a recent, anthropological turn I have explored through numerous articles and a recent, co-authored book (Collins and Durington 2024). In anthropology, multimodality recognizes the anthropological practice in non-anthropologists as they seek to document, represent their communities, and intervene in the futures of those places. People are ultimately anthropologists of their own lives, and I have helped to develop a methodology that integrates this insight into a more collaborative, and more de-centered work that considers multiple, community-produced media alongside more “official” anthropological analysis (Collins and Durington 2015; Collins and Durington 2024). Here, I propose looking to neighborhood identity as a collaborative, negotiated and occasionally fraught negotiation of meaning, place and identity. My insights have been very much informed by fieldwork - in South Korea and in Baltimore. And it’s these same insights that I propose to bring into the classroom in a series of methodologically focused, participatory courses that task students with documenting the anthropologies of their own communities. What I hope to accomplish through this research and teaching will ultimately work towards an understanding of global processes in an age where the physical and the digital occupy overlapping spheres in the lives of people and in the futures of communities.

Precursors

Years ago, I became interested in a general nostalgia for the narrow streets and claustrophobic spaces of older neighborhoods, including “taldongne” (달동네)—clusters of homes that originated as unofficial housing in the heavy urban migrations after the Korean War, and that are characterized by a lack of planning and infrastructure. Perhaps the most iconic moment for me was the huge popularity of the “Reply 1988” (응답하라 1988), a nostalgic, family drama/comedy that unfolds against the backdrop of the Seoul 1988 Olympics and takes place in a modest neighborhood of 1970s-era homes and narrow streets. The end of the series finds the old neighborhood abandoned and slated for re-development–and end to a more simple time. Indeed, by the 1970s, many of the residents of older neighborhoods were being forcibly (and even violently) evicted, and large-scale apartment developments put up in their place. This trend accelerated through the early 21st century with the establishment of “new town” developments radically transforming the urban fabric of multiple South Korean cities. Predictably, perhaps, the disappearance of these older, largely working-class neighborhoods was accompanied by a longing for community and an appreciation for these organic, eclectic spaces, in dramatic contrast to the huge developments that now house the majority of people in Korea.

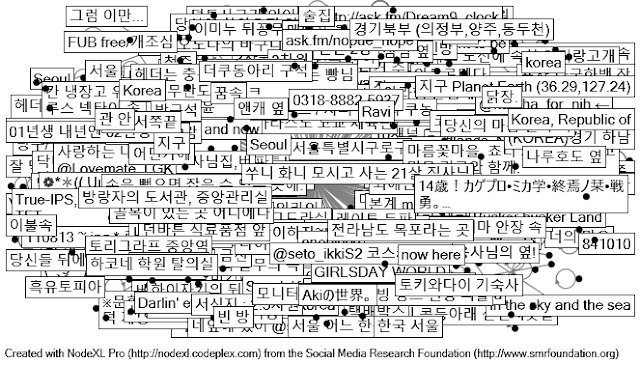

That nostalgia extends across multiple media, from television and film to webtoons, games and apps—and, of course, social media, where the search for selfies and more aesthetic photography sends millions of domestic and international tourists to the few, extant working-class neighborhoods in search of the perfect pictures for their Instagram accounts. In my 2014-2015 fieldwork, I analyzed numerous “alleyway” social media accounts, and set off with local photography clubs (1 Korean, 1 Korean and non-Korean), taking pictures of narrow streets, rusted grates and broken latticework. Globally, the neighborhoods are iconic, connoting “Korea” even as their existence fades from Korea’s urban fabric; it would be difficult to find a k-drama that didn’t have some romantic moment set in one of these places. Yet the vast majority of Koreans have never lived in them.

Nevertheless some neighborhoods still remain. My previous work in Seoul coincided with a period of relative openness in the form of urban regeneration policies that were just beginning under the leadership of then-Mayor Park Won Soon (Nam and Lee 2023). Through government programs, non-profits and museum exhibitions, people in Seoul looked to these communities as something that deserved, at least, some measure of preservation–in sharp distinction to the policies of Park’s predecessors that had accelerated the frenetic pace of urban redevelopment. Along with this came calls for a more textured and genuine urban life where people might develop attachments to each other and to their neighborhoods (Lee 2011). Along the way, new public spaces, sidewalks, and parks were all constructed to make Seoul a more livable city.

Yet, people in older neighborhoods must still negotiate with the combination of touristification and gentrification that have encroached upon their lives. Touristification in the form of busloads of people coming to neighborhoods that were once avoided by non-residents, and gentrification in the form of up-scale teashops and bars that have grown up in “edgy” and “artistic” areas. There are a variety of means to resist these forces, but I became interested in the ways that residents have utilized diverse media in order to form counter-representations of life that contest the romantic commodification from tourism and, to some extent, from the state. YouTube, film and podcasts are generated alongside print magazines, gallery shows and other events in order to give voice to residents and to underline their placemaking. The irony here—and there are many ironies—is that, in their resistance, residents are instantiating the very community ethos over which people and media have waxed nostalgic.