Occasional posts on anthropologically interesting science fiction, anthropological futures and my own future as an anthropologist.

Showing posts with label Baltimore. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Baltimore. Show all posts

Monday, June 6, 2022

20th Anniversary of HBO's "The Wire"

In 2011, we started a project entitled "Anthropology By the Wire" with participants drawn mainly from community colleges in the Baltimore area. Our goal was to collaborate with neighborhood-based groups in Baltimore to make anthropologically informed representations of their communities that they could utilize for their own purposes. My co-PI for the project, and my co-author, Matt Durington, explains the whole process in this 2011 video on the YouTube channel for the project. We meant it as a critique of "The Wire"--or, at least, the way "the Wire" had come to stand in for documentary truths about the city. Circling back to the series 20 years, and our project 10 years later, I find that not much has changed. The series continues to have this representational hegemony and, in many ways, still pushes to the sides other representations of Baltimore not grounded in policing and heavily demonized images of drugs and crime.

"The Wire" presented audiences with a superbly acted, nuanced portrait of Baltimore - certainly the most complex mass media representation to date. But it was, in the end, mass media grounded in a white perspective that wants to see Baltimore as a spectacle of abandonment and violence. Yet there were moments when the city seemed to exceed that perspective - when neighborhoods themselves took the stage. Those were our favorite scenes. I know that the camera "wanted" us to see the boarded up houses, weeds and trash - but there are times when we saw the small-scale intimacy of neighborhoods and the interpenetrations of lives in "Smalltimore." As anthropologists, what "The Wire" made us realize is that communities could represent themselves. Also, as time went on, technologies (smart phones, social media) that would help people do that became more and more available. "Anthropology By the Wire" was about building collaborative media with people in neighborhoods to tell stories they wanted to tell in ways that made sense to them. It was piecemeal, production values varied, and, of course, there was no script. In that sense, it was the opposite of "The Wire." But it was still generated in the space opened up by "The Wire."

Monday, August 15, 2016

Tales From the Remix Anthropologist

For anthropology, remix always sounded better than it looked in practice. After all, even though it is hard to argue with Jenkins's writings on "Remix culture," it always seemed to mean more for music, art, literature and--primarily--for popular culture. In anthropology, what does "remix" mean? Does it mean self-plagiarism? Does it mean taking images or media and re-using them in other contexts? Colonialism and cultural appropriation under another name? As my colleague Matthew Durington and I write in our book, Networked Anthropology (70):

When we started our Anthropology By the Wire project--an NSF-funded effort to build a large corpus of collaborative media about neighborhoods in Baltimore--we naturally gravitated to a Creative Commons license--but we couldn't go the final step towards the "gold standard," one that "lets others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon your work." Given the power inequalities and rampant racism of contemporary life in the U.S., it seemed too dangerous--and even unethical--to subject our work with communities in Baltimore to this kind of remix.

Needless to say, like us, other anthropologists have not been especially eager to enjoin remix in their own work, although they've certainly had their own work remixed by others, as when footage from Adam Fish got remixed for pro-Palestinian hip-hop. Sometimes anthropologists have invited remix, as Chris Kelty did after the open source/ creative commons Two Bits was published. In good, open-source fashion, the book was "ported" by readers onto different platforms, but that seems to have been the limits to the monograph's "remix"--beyond that of traditional scholarly remix whereby influential texts shape the scholarship that comes after them.

Despite these somewhat tepid engagements with remix, and the ethical responsibilities we owe the communities with whom we work, we believe that remix can offer anthropologists some important possibilities, but not in the ways, perhaps, that Lessig and Jenkins originally envisioned. Instead, we decided to remix ethnographic data about the community with members of the community. To create, in other words, derivative works about our work with our community collaborators in order to better disseminate anthropological media to audiences on a different platform.

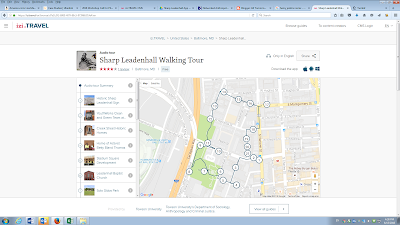

From 2013 until now, we've been experimenting with different app platforms, including ARIS and MIT App Inventor. These both support geo-located apps, and we've produced some apps about Baltimore. But the big impetus for our app remix has come in the form of a structured, plug-and-play platform for tour apps called "izi.travel". It's readily available on Android or iOS platforms and is free (although not open source). While it lacks the programmable interface of MIT App Inventor, it makes up for it in the capacity to upload multimedia onto the app, including text, video, photograph and audio, all accessible through a geolocated map. With izi.travel, we move from a miscellany of media about a South Baltimore neighborhood to a remixed, multimodal experience that engages app users on multiple cognitive and sensorial levels.

There are several things to keep in mind when making your anthropological media into an app: 1) your media is going to be experienced by people walking around with a smartphone, so it needs to be short and simple: brief interviews, short clips, terse historical notes. 2) Smartphones allow you to use audio as well as visual media--take advantage of this by including some interview material with interlocutors and by turning some of your narrative into an audio tour. 3) Include notes on directions! Even though our app comes with a Google map embedded in the smartphone interface, it's reassuring to have someone tell you to "turn right at the corner"--especially when you're encountering a neighborhood for the first time!

In addition, there are several things are worth pointing out. First, our app is free and the content we've loaded up is under a creative commons license. Second, we produced the app with the same people we've worked with during Anthropology By the Wire--i.e., the derivative remix is also a collaborative work. Third, we agree, as part of our ethical commitment to our interlocutors, to monitor how this multimedia data is utilized. As we say in the our letter of consent (vetted by our institution's IRB):

For anthropology, the problem of remix isn't that it's so new, but that it's so old. What seems progressive and egalitarian when it comes to creating parodies of repressive legislation or "culture jamming" corporate hegemony looks decidedly less so when we apply the ethic to what gets defined as culturally or socially "other."Given the past of Western anthropology, it is not especially surprising that remix hasn't taken off in anthropological circles--it looks too much like what we've been doing since the 18th century. The "freedom" to take content out of one context and place it into another looks more like oppression when it's practiced on ethnographic data gathered about people who are routinely denied the means for their own self-representation.

When we started our Anthropology By the Wire project--an NSF-funded effort to build a large corpus of collaborative media about neighborhoods in Baltimore--we naturally gravitated to a Creative Commons license--but we couldn't go the final step towards the "gold standard," one that "lets others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon your work." Given the power inequalities and rampant racism of contemporary life in the U.S., it seemed too dangerous--and even unethical--to subject our work with communities in Baltimore to this kind of remix.

Needless to say, like us, other anthropologists have not been especially eager to enjoin remix in their own work, although they've certainly had their own work remixed by others, as when footage from Adam Fish got remixed for pro-Palestinian hip-hop. Sometimes anthropologists have invited remix, as Chris Kelty did after the open source/ creative commons Two Bits was published. In good, open-source fashion, the book was "ported" by readers onto different platforms, but that seems to have been the limits to the monograph's "remix"--beyond that of traditional scholarly remix whereby influential texts shape the scholarship that comes after them.

Despite these somewhat tepid engagements with remix, and the ethical responsibilities we owe the communities with whom we work, we believe that remix can offer anthropologists some important possibilities, but not in the ways, perhaps, that Lessig and Jenkins originally envisioned. Instead, we decided to remix ethnographic data about the community with members of the community. To create, in other words, derivative works about our work with our community collaborators in order to better disseminate anthropological media to audiences on a different platform.

From 2013 until now, we've been experimenting with different app platforms, including ARIS and MIT App Inventor. These both support geo-located apps, and we've produced some apps about Baltimore. But the big impetus for our app remix has come in the form of a structured, plug-and-play platform for tour apps called "izi.travel". It's readily available on Android or iOS platforms and is free (although not open source). While it lacks the programmable interface of MIT App Inventor, it makes up for it in the capacity to upload multimedia onto the app, including text, video, photograph and audio, all accessible through a geolocated map. With izi.travel, we move from a miscellany of media about a South Baltimore neighborhood to a remixed, multimodal experience that engages app users on multiple cognitive and sensorial levels.

There are several things to keep in mind when making your anthropological media into an app: 1) your media is going to be experienced by people walking around with a smartphone, so it needs to be short and simple: brief interviews, short clips, terse historical notes. 2) Smartphones allow you to use audio as well as visual media--take advantage of this by including some interview material with interlocutors and by turning some of your narrative into an audio tour. 3) Include notes on directions! Even though our app comes with a Google map embedded in the smartphone interface, it's reassuring to have someone tell you to "turn right at the corner"--especially when you're encountering a neighborhood for the first time!

In addition, there are several things are worth pointing out. First, our app is free and the content we've loaded up is under a creative commons license. Second, we produced the app with the same people we've worked with during Anthropology By the Wire--i.e., the derivative remix is also a collaborative work. Third, we agree, as part of our ethical commitment to our interlocutors, to monitor how this multimedia data is utilized. As we say in the our letter of consent (vetted by our institution's IRB):

If you do choose to allow us to place text, audio, photographs and/or film online, then we promise to monitor this content using different tools in order to find out how the material is being received, and how it's being used. Similarly, if you discover that media we've made together is being used in a way you find inappropriate, please contact us immediately. (from Networked Anthropology, p. 128)The final product is the "Sharp Leadenhall Walking Tour". What we hope we've produced is something that is anthropologically dense and critical, but that still gives people an opportunity to discover a beautiful neighborhood!

Saturday, May 21, 2016

Zombie in the Armchair: Anthropologists as Connective Agents

One of the community groups we work with has a book out. Another has just won a major victory for environmental justice. A third is looking for new staff. Another has posted an incredible collection of photos from the Baltimore Uprising. My responses? Depending on the social media platform, “Like”; “Retweet”; “Share”; “Follow”. Perhaps those aren’t even “responses”. I haven’t done anything—I haven’t even moved from my chair! Even J.G Frazer had to get up to pick up another tome of hermetic folklore. But I would be remiss not to engage in this slacktivism. Not only remiss, I would be endangering our relationship to our Baltimore interlocutors. Public anthropology takes many forms—including advocate, gadfly and cultural critic. What about zombie?

The digital, networked world in which we live has enabled unparalleled access to the tools of content creation. All of us can make a movie, write a novel, publish photographs; after all, “Web 2.0” is supposed to blur the distinction between producer and consumer. But for every would-be filmmaker who uploads their work on YouTube, there needs to be agents that propagate media through a network. This is the moral dilemma of slacktivism: despite the particularly tepid support a “like” or a “share” represents, political action undertaken through digital networks require agents to “route” messages through their own networks, and to do so while limiting their own commentary or added content. In other words, digital creators need armies of people to pass along messages to all of their friends. Conversely, they don’t need other people to appropriate and remix their message—they just need us to do what we’re told. To go back to my examples above, it would seem inappropriate and disingenuous to piggy-back on my informants’ successes with my own self-aggrandizing thoughts: “Nice photos. See my recent article on de-industrialization in Baltimore for more context.” Shouldn’t I just pass these social media along? Without subjecting them to my own hermeneutic violence? In other words, the Internet needs mindless zombies.

I’ve been reading Tony Sampson’s Virality: Contagion Theory in the Age of Networks and find much there for anthropologists to consider in terms of their own work. Nineteenth century social theorists were keenly interested in this process of creation and contagion; in an era of social unrest and popular rebellion, it was a symptom of their fear of “the crowd.” In Gabriel Tarde’s formulation, the crowd could be explained with reference to an “imitative ray” that “comprises of affecting (and affected) noncognitive associations, interferences and collisions that spread outward, contaminating feelings and moods before influencing thoughts, beliefs, and actions” (Sampson 2012: 19). Tarde’s subjects “sleepwalk through everyday life” (ibid., 13), the unwitting host to a parasitical message that will leap from them to other sleep-walking subjects along a networked chain of imitation. In their urge-to-imitate and reproduce, subjects leave their free will behind. In Sampson’s terms, “Social man is a somnambulist” (13).

It is safe to say that this is not how most anthropologists would like to be described. We are, after all, the ones who are supposed to be doing the interpreting. Our informants may produce anthropologically intended media, they may interview each other, and they may post insightful commentary; but these are data that wait for us to collect, collate, analyze, interpret and publish. Even if we do so for all of the right, public anthropology reasons, we very much mean to have the last word; this will-to-subjectivity is readily evident in the texts and media we create. Critical of rational choice theory and Western, 19th century models of subjectivity, anthropologists rest on their authority to create, to measure, to rationate. Moreover, the qualities of the zombie—passivity, submission, thoughtlessness—are also associated with the terrifying domination of the person under advanced capitalism. We live in a world where increasing numbers of people have had their own wills ripped away away from them as they are forced into prisons, migrant camps, homelessness. And at the same time, Tarde’s “imitative rays” have been harnessed by corporate capital in order to denude all of us of our capacity to judge for ourselves.

But there is another side to Tarde’s model, one where imitation is still premised on a mutual relationship. Sampson continues:

Tarde’s notion of hypnotic obedience reveals a complex reciprocal relationship in which subjects are not simply controlled by deep-seated fears and phobias but also tend to copy (on the surface) those whom they love or at least empathize with. (170)Obviously, this can (and certainly is) manipulated by corporations and governments, but the relationship need not only be one-sided. Our own, social media lives suggest a more egalitarian relationship. Our friends post something—we duly send it along. We post something, and we expect that they will do the same. We are all full of pithy, political insights, hilarious jokes, mad photo-shopping skills: we deserve to be copied, shared, re-posted. In the age of social media, to be friends means to be ready to take the role of the zombie.

For anthropologists, this means that sometimes we may be the imitated, and sometimes the imitator. After all, our informants may not always need our sagacity—but they will always need our support. And that support will take many forms, some more active and agential than others. But following our informants is an important role, indispensable to a networked world. Sometimes, in other words . . . BRAINS . . . .

Saturday, January 23, 2016

Right to the City in Baltimore and Design Anthropology

Note: the narrative for my Design Anthropology class for Spring 2016.

People in Baltimore demand a “right to the city,” i.e., to live in a city that allows them to develop human and community potentials without pernicious race- and class-based inequalities. But, a year after the Baltimore Uprising, we are still confronting the city’s systematic, structural inequalities. And while there are numerous (pressing) injustices to be addressed, one of the most challenging questions we could ask people in power is simply that: where is the “right to the city” for the majority of Baltimore’s residents?

This doesn’t mean the right to buy and consume in Baltimore’s tourism spaces. Instead, it’s about heretofore marginalized peoples “fighting for the kind of development that meets their needs and desires” (Harvey 2013: xvi). And not just in the short term. As Henri Lefebvre wrote in the shadow of the Paris Commune, “To the extent that the contours of the future city can be outlined, it could be defined by imagining the reversal of the current situation, by pushing to its limits the converted image of the world upside down” (Lefebvre 1967: 172).

In other words, it’s about imagining radical alternatives to the city. To re-forge it, in Robert Park’s words, into “the heart’s desire” for the ordinary citizens of the city, rather than for a handful of the wealthy and privileged. This is the challenge for anthropology. Despite the growth of a public anthropology, the field still often divides into a theoretical concern with power and politics, on the one hand, and an applied anthropology that packages its portmanteau methods for sale, on the other. In public anthropology, critical interventions are oftentimes uncomfortably grafted onto traditional, descriptive research—a sometimes grudging admission that anthropology may contribute to the public weal. But how do we forge an anthropology where political change is part of our methodical and theoretical approach from the outset, rather than the newspaper editorial that may follow the publication of an ethnographic monograph?

This is our challenge: to imagine a design anthropology that originates in “the cry and the demand” of the disenfranchised (Lefebvre 1967: 158). Moreover, it must be premised on the practice of radical alternatives to the status quo. It cannot be an accommodation to power in the form of bland palliatives to inequality. Instead, design anthropology must take the “right to the city” as a call for dismantling the institutions that reproduce inequality and re-building a city where, as Harvey writes, we can claim the “freedom to make and remake ourselves and our cities” (Harvey 2013: 4).

Doing this means re-imagining anthropology as well. If we would like to “restore design to the heart of anthropology’s disciplinary practice” (Gatt and Ingold 2013: 140), then we must also dismantle the hoary dichotomies that have undermined possibilities for an anthropology defined by political practice. Doing thus may be achievable through a design anthropology infused with a Bloch-ian hope for alternative possibilities. And through this, we may be able to sketch the possibility for an anthropology that engages what it really means to be human, i.e., to be a person desirous of a better world.

This class will explore design anthropology through its relevance to the continuing struggle of people in Baltimore to achieve justice and equality. We begin with a critique of Baltimore’s top-down developmental model, one that has given the city temples to capital (Charles Center and the Legg-Mason Building) and hollow quotations of urban life in tightly scripted, touristic spaces structured to exclude the majority of Baltimore’s residents (Inner Harbor, Camden Yards, Canton). From there, we consider a series of design interventions that were accomplished through various participatory structures: community gardens, bikeshare programs, community mapping, digital storytelling. But even these, as we shall explore after the midterm, ultimately buttress the system they purport to critique—they “humanize” the developmental city without challenging the institutions and practices that invariably privilege elites. From this realization, we move to a literature demanding something more than the mollification of Baltimore’s citizens. These “guerilla” urbanisms point towards the efficacy of direct action in creating a just city. Finally, we return to an insistence on utopia, not in terms of some fixed version of perfection, but as an evocation of virtualities that we may not be able to fully articulate, possibilities of a new “urban being” just over the horizon of our political consciousness.

People in Baltimore demand a “right to the city,” i.e., to live in a city that allows them to develop human and community potentials without pernicious race- and class-based inequalities. But, a year after the Baltimore Uprising, we are still confronting the city’s systematic, structural inequalities. And while there are numerous (pressing) injustices to be addressed, one of the most challenging questions we could ask people in power is simply that: where is the “right to the city” for the majority of Baltimore’s residents?

This doesn’t mean the right to buy and consume in Baltimore’s tourism spaces. Instead, it’s about heretofore marginalized peoples “fighting for the kind of development that meets their needs and desires” (Harvey 2013: xvi). And not just in the short term. As Henri Lefebvre wrote in the shadow of the Paris Commune, “To the extent that the contours of the future city can be outlined, it could be defined by imagining the reversal of the current situation, by pushing to its limits the converted image of the world upside down” (Lefebvre 1967: 172).

In other words, it’s about imagining radical alternatives to the city. To re-forge it, in Robert Park’s words, into “the heart’s desire” for the ordinary citizens of the city, rather than for a handful of the wealthy and privileged. This is the challenge for anthropology. Despite the growth of a public anthropology, the field still often divides into a theoretical concern with power and politics, on the one hand, and an applied anthropology that packages its portmanteau methods for sale, on the other. In public anthropology, critical interventions are oftentimes uncomfortably grafted onto traditional, descriptive research—a sometimes grudging admission that anthropology may contribute to the public weal. But how do we forge an anthropology where political change is part of our methodical and theoretical approach from the outset, rather than the newspaper editorial that may follow the publication of an ethnographic monograph?

This is our challenge: to imagine a design anthropology that originates in “the cry and the demand” of the disenfranchised (Lefebvre 1967: 158). Moreover, it must be premised on the practice of radical alternatives to the status quo. It cannot be an accommodation to power in the form of bland palliatives to inequality. Instead, design anthropology must take the “right to the city” as a call for dismantling the institutions that reproduce inequality and re-building a city where, as Harvey writes, we can claim the “freedom to make and remake ourselves and our cities” (Harvey 2013: 4).

Doing this means re-imagining anthropology as well. If we would like to “restore design to the heart of anthropology’s disciplinary practice” (Gatt and Ingold 2013: 140), then we must also dismantle the hoary dichotomies that have undermined possibilities for an anthropology defined by political practice. Doing thus may be achievable through a design anthropology infused with a Bloch-ian hope for alternative possibilities. And through this, we may be able to sketch the possibility for an anthropology that engages what it really means to be human, i.e., to be a person desirous of a better world.

This class will explore design anthropology through its relevance to the continuing struggle of people in Baltimore to achieve justice and equality. We begin with a critique of Baltimore’s top-down developmental model, one that has given the city temples to capital (Charles Center and the Legg-Mason Building) and hollow quotations of urban life in tightly scripted, touristic spaces structured to exclude the majority of Baltimore’s residents (Inner Harbor, Camden Yards, Canton). From there, we consider a series of design interventions that were accomplished through various participatory structures: community gardens, bikeshare programs, community mapping, digital storytelling. But even these, as we shall explore after the midterm, ultimately buttress the system they purport to critique—they “humanize” the developmental city without challenging the institutions and practices that invariably privilege elites. From this realization, we move to a literature demanding something more than the mollification of Baltimore’s citizens. These “guerilla” urbanisms point towards the efficacy of direct action in creating a just city. Finally, we return to an insistence on utopia, not in terms of some fixed version of perfection, but as an evocation of virtualities that we may not be able to fully articulate, possibilities of a new “urban being” just over the horizon of our political consciousness.

Friday, July 5, 2013

Friending the Man of the Crowd

| |

| Illustration for Edgar Allan Poe's story "The Man of the Crowd" by Harry Clarke (1889-1931), first printed in 1923 (from Wikimedia Commons) |

Edgar

Allan Poe’s story fragment, “The Man of the Crowd” (published in 1840 when Poe

was living between Baltimore, Richmond and Philadelphia), begins with the

narrator peering out onto a London street from a café, making observations

about passersby: typologies of urban dwellers (“the tribe of clerks,” the “race

of swell pick-pockets”), divisions of the population into age, gender, race and

ethnicity. Finally, though, his gaze

alights on an enigmatic character that eludes easy classification: “decrepit”

and “feeble,” yet “he rushed with an activity I could not have dreamed of

seeing in one so aged”; “without apparent aim,” yet characterized by “blood

thirstiness” and armed with a “dagger”.

Seduced by these paradoxical attributes, Poe’s narrator follows the man

until sunrise, without, though, gaining any insight into the man’s history, nor

of his ultimate aims.

Within this brief fragment, we can

see multiple approaches to the urban collide: the first, the assignation of

types. The second, an ethnographic

approach premised on direct observation of a single individual walking the

streets. One attempts to make sense of

the whole—to say something, in this case, about London’s (or Baltimore’s or Philadelphia’s)

urban population and the growth of a heterosocial, public space in the mid-19th

century (Walkowitz 1992). The second,

the specificity of the individual in a particular place: what one could call the

“daily round” of the individual. But

both approaches prove inadequate to understanding the enigmatic man of the

crowd.

But what if Poe’s narrator had tried

a network approach? What if one could

show that the man of the crowd’s apparently aimless wanderings were, instead,

the outlines of a networked city connecting multitudes of nodes consisting of

places and people? What if one could

analyze those connections? As many have

shown, the city is, literally, the sum of its networks, assemblages of place

and connection that are simultaneously larger and smaller than the

geo-political boundaries of the urban (Pflieger and Rozenblat 2010). Within this concatenation, people and place

can be connected in myriad ways: the “strong” and “weak” ties that form the

basis of much of social network analysis, but also in the form of a variety of “latencies”

that, as Haythornthwaite (2002: 389) suggests, multiply in the age information and

communication technologies and add new potentials to the elaboration of the

urban networks around us. In a networked

world, Poe’s narrator might be able to exploit these connections in order to connect

to his man in the crowd and make sense of his world.

And, indeed, this is what happens

all of the time in urban life. Armed

with various ICT’s (information and communication technologies), people trace

complicated networks that include physical structures, transportation, socialites,

technologies, economies and symbolic communications. But by tweeting (or using me2day or yozm),

posting to blogs, utilizing geolocational apps and uploading photos and videos,

people multiply possibilities for place- and sense-making, mobilizing virtual connections

that might open up new possibilities for physical or spatial connections, that might make the strange into the famiilar.

This is an important difference from Poe's time. Poe's "man of the crowd" and Baudelaire's "flaneur" depend upon a uniquely urban condition: spending one's life surrounded by complete strangers. On the other hand, in our ICT-inflected lives, nobody can be a "complete" stranger. Rather, in the fuzzy logic of social media, people on the street present different quanta of latency--different potentialities of connection that we may or may not be able to exploit. When we attend a rally and marvel at the disparate groups that (momentarily) cohere in a place, we're witnessing the activation of some of those latent ties, and, most probably, their rapid dissolution.

Thursday, October 4, 2012

"By the Wire," not "Through the Wire"

It has been 10 years since David Simon's "The Wire" premiered on HBO. A product of Simon's long-time partnership with Ed Burns, a retired Baltimore City homicide detective, "The Wire" presented Baltimore through the lens of police officers, drug dealers, troubled children, educators. A Dickensian drama-from-below, Simon's series grew more and more complex through its five seasons. Actively working to challenge easy interpretations of Baltimore's problems, Simon refused to indulge in the usual media reduction of urban life to pathologized caricatures.

Over those 10 years, some anthropologists began to include "The Wire" in their courses, presumably because they found it ethnographically interesting. And it is, but not because it offers an empirical "window" onto the lives of Baltimore's urban poor. Instead, "The Wire" is interesting because it presents the complexities of white, middle-class perspectives on race and social class. It lays bare the tortured contradictions, the logical inconsistencies of dominant theoretical perspectives, from the neo-liberal, rational choice theory used to interpret some of The Wire's more larger-than-life drug-dealers, to the structural interpretations examining the inequalities of education in the city. Ultimately, though, the series remains trapped in the puzzle-box of the racialized other, and the failure of the series to indict the neo-liberal (although Simon certainly tried) points to the inabilities of US intellectuals to conceptualize both race- and class inequality. Bouncing between reformer, radical and reactionary, "the Wire" is probably the best portrait we have today of U.S. urban policy, one that accurately represents the hypostatized contradictions urban lawmakers and pundits bounce impotently between in their perpetual efforts to prescribe a "cure" to the problem of the urban.

In that sense, Peter Beilenson's and Patrick McGuire's Tapping Into The Wire: The Real Urban Crisis (The Johns Hopkins Press, 2012), is a logical next step. In a series of reflections on his 13 years as Baltimore's public health commissioner (1992-2005), Beilenson examines scenes and characters in The Wire as synecdoches of public health problems inflicting US cities. As he reflects, "I realized then that it was a perfect crystallization of all of the public health and social problems I had faced in real-life Baltimore during my thirteen years as health commissioner" (4).

Each chapter focuses on a health problem (drugs, STD's, HIV), and Beilenson's response to it as commissioner. Some of these stories are heroic--e.g., Beilenson's needle-exchange program and his work on a plan for universal health care for Baltimore. Some, less so. In fact, my only memory of Beilenson during his tenure is his infamous support for Norplant, a birth-control implant that he wanted to offer to at-risk teens, a plan that led to charges of eugenics. Later, there was similar controversy over Depo-Provera. Here, he defends those programs, and there is little doubt that he had the City's best interests at heart. But he still comes across as disingenuously political. As he writes,

Still, Beilenson's anecdotes are reminders that enlightened public health policy can make concrete changes in the lives of people, and that so many of the things conservatives interpret as the intransigent moral failing of individuals are, in fact, public health problems that impact all of us. Perhaps we can bring Beilenson back from Howard County (where he continues as health officer of Howard County).

But Tapping Into the Wire also sharply contrasts with our approach in Anthropology By the Wire. Ultimately, Beilenson and McGuire still take their cues from The Wire and, by extension, hegemonic representations of Baltimore in mass media that define the city and its citizens as a series of problems, as a negative values in indicators for health, education and crime. The difference: we're starting from the opposite end, building media that begin with people's lives and experiences, not in order to provide fodder for political pathologizations, but to help people represent themselves to each other, and to other institutions and agents of change who might be of benefit to them. In other words, "By The Wire": in the same places, the same neighborhoods, but getting an altogether different story.

Over those 10 years, some anthropologists began to include "The Wire" in their courses, presumably because they found it ethnographically interesting. And it is, but not because it offers an empirical "window" onto the lives of Baltimore's urban poor. Instead, "The Wire" is interesting because it presents the complexities of white, middle-class perspectives on race and social class. It lays bare the tortured contradictions, the logical inconsistencies of dominant theoretical perspectives, from the neo-liberal, rational choice theory used to interpret some of The Wire's more larger-than-life drug-dealers, to the structural interpretations examining the inequalities of education in the city. Ultimately, though, the series remains trapped in the puzzle-box of the racialized other, and the failure of the series to indict the neo-liberal (although Simon certainly tried) points to the inabilities of US intellectuals to conceptualize both race- and class inequality. Bouncing between reformer, radical and reactionary, "the Wire" is probably the best portrait we have today of U.S. urban policy, one that accurately represents the hypostatized contradictions urban lawmakers and pundits bounce impotently between in their perpetual efforts to prescribe a "cure" to the problem of the urban.

In that sense, Peter Beilenson's and Patrick McGuire's Tapping Into The Wire: The Real Urban Crisis (The Johns Hopkins Press, 2012), is a logical next step. In a series of reflections on his 13 years as Baltimore's public health commissioner (1992-2005), Beilenson examines scenes and characters in The Wire as synecdoches of public health problems inflicting US cities. As he reflects, "I realized then that it was a perfect crystallization of all of the public health and social problems I had faced in real-life Baltimore during my thirteen years as health commissioner" (4).

Each chapter focuses on a health problem (drugs, STD's, HIV), and Beilenson's response to it as commissioner. Some of these stories are heroic--e.g., Beilenson's needle-exchange program and his work on a plan for universal health care for Baltimore. Some, less so. In fact, my only memory of Beilenson during his tenure is his infamous support for Norplant, a birth-control implant that he wanted to offer to at-risk teens, a plan that led to charges of eugenics. Later, there was similar controversy over Depo-Provera. Here, he defends those programs, and there is little doubt that he had the City's best interests at heart. But he still comes across as disingenuously political. As he writes,

Although certainly not the only reason, I think it is clear that the provision of contraception in our school-based health centers helped Baltimore drop from having the highest teen birth rate in the country to the number 15 ranking: over the past twenty years, the city's teen birth rate dropped by more than 40 percent. (118)First, there's a suspicious, semantic shift from Norplant and Depo-Provera to general contraception. I think making contraception available in schools is an important intervention--but which ones? Second, it's unclear how much these interventions are responsible for dropping teen birth rates. Teen pregnancies have been dropping nationally by about 3 percent per year since 1991. The CDC is not entirely certain why this rate has dropped, and it seems like a bit of shell game to suggest that Norplant led to the Baltimore decline.

Still, Beilenson's anecdotes are reminders that enlightened public health policy can make concrete changes in the lives of people, and that so many of the things conservatives interpret as the intransigent moral failing of individuals are, in fact, public health problems that impact all of us. Perhaps we can bring Beilenson back from Howard County (where he continues as health officer of Howard County).

But Tapping Into the Wire also sharply contrasts with our approach in Anthropology By the Wire. Ultimately, Beilenson and McGuire still take their cues from The Wire and, by extension, hegemonic representations of Baltimore in mass media that define the city and its citizens as a series of problems, as a negative values in indicators for health, education and crime. The difference: we're starting from the opposite end, building media that begin with people's lives and experiences, not in order to provide fodder for political pathologizations, but to help people represent themselves to each other, and to other institutions and agents of change who might be of benefit to them. In other words, "By The Wire": in the same places, the same neighborhoods, but getting an altogether different story.

Thursday, August 21, 2008

Future Baltimore!

It's pretty hard to imagine a more Gothic city than Baltimore (in the literary sense). You've got the Faulkner-esque kind of gothic with over-grown gardens, crumbling shacks, shambling, sclerotic citizens. And also the northern gothic--shuttered factories, menacing turrets on decrepit mansions, etc. It is no particular wonder why Baltimore is often the preferred mise-en-scene for mystery novels.

But it's harder to envision a futuristic Baltimore. The usual urban boosters (e.g., Live Baltimore, The Urbanite) do their best, but I don't know of any sf novel set in the city--even cyberpunk dystopias of the near future seem to have passed us by. Still, I would like to try to evoke stochastic, interesting futures for my city.

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, Margaret Mead often theorized about the ingredients of the creative city—the institutions that she thought might stimulate what she called “emergent clusters”. But the point to her analysis—and to what I think today—is that neither what elements might be important nor the resulting “clusters” can be known in advance. What we can do is to multiply opportunities for creative crossings of all kinds—not just forms that we’ve determined in advance (festivals, galleries, literary salons)—but the ones that will emerge just beyond the borders of our predictions. The point is to open connections between peoples and parts of life in our city that have been historically separated—by race, religion, language, location, orthodoxy and heterodoxy. In Baltimore, this would first involve identifying the configurations with the most potent potentialities for emergence, and then assist in the creation of the space for those connections to grow, a catalog of potentials, rather like Doni’s 15th century catalog of books that had not yet been written. When we imagine the best that Baltimore can be, aren’t we excluding what we can’t yet imagine? This is the difference, I think, between urban areas that emerge as poster children for the creative class and ones that continuously run to catch up.

But it's harder to envision a futuristic Baltimore. The usual urban boosters (e.g., Live Baltimore, The Urbanite) do their best, but I don't know of any sf novel set in the city--even cyberpunk dystopias of the near future seem to have passed us by. Still, I would like to try to evoke stochastic, interesting futures for my city.

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, Margaret Mead often theorized about the ingredients of the creative city—the institutions that she thought might stimulate what she called “emergent clusters”. But the point to her analysis—and to what I think today—is that neither what elements might be important nor the resulting “clusters” can be known in advance. What we can do is to multiply opportunities for creative crossings of all kinds—not just forms that we’ve determined in advance (festivals, galleries, literary salons)—but the ones that will emerge just beyond the borders of our predictions. The point is to open connections between peoples and parts of life in our city that have been historically separated—by race, religion, language, location, orthodoxy and heterodoxy. In Baltimore, this would first involve identifying the configurations with the most potent potentialities for emergence, and then assist in the creation of the space for those connections to grow, a catalog of potentials, rather like Doni’s 15th century catalog of books that had not yet been written. When we imagine the best that Baltimore can be, aren’t we excluding what we can’t yet imagine? This is the difference, I think, between urban areas that emerge as poster children for the creative class and ones that continuously run to catch up.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Stuck in the Turing Matrix - Arxiv Pre-print

Stuck in the Turing Matrix: Inauthenticity, Deception and the Social Life of AI Samuel Gerald Collins ...

-

[From the SETI project, "A Sign in Space" ( https://asignin.space/ )] “To interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world — in...

-

(from our storymap ) In my capacity as a fellow in our faculty research center, I've been doing a lot of support work for the u...

-

An article in the Baltimore Banner by Rona Kobell ( https://www.thebaltimorebanner.com/community/local-news/hampton-national-historic-site-e...