For anthropology, remix always sounded better than it looked in practice. After all, even though it is hard to argue with Jenkins's writings on "Remix culture," it always seemed to mean more for music, art, literature and--primarily--for popular culture. In anthropology, what does "remix" mean? Does it mean self-plagiarism? Does it mean taking images or media and re-using them in other contexts? Colonialism and cultural appropriation under another name? As my colleague Matthew Durington and I write in our book,

Networked Anthropology (70):

For anthropology, the problem of remix isn't that it's so new, but that it's so old. What seems progressive and egalitarian when it comes to creating parodies of repressive legislation or "culture jamming" corporate hegemony looks decidedly less so when we apply the ethic to what gets defined as culturally or socially "other."

Given the past of Western anthropology, it is not especially surprising that remix hasn't taken off in anthropological circles--it looks too much like what we've been doing since the 18th century. The "freedom" to take content out of one context and place it into another looks more like oppression when it's practiced on ethnographic data gathered about people who are routinely denied the means for their own self-representation.

When we started our Anthropology By the Wire project--an NSF-funded effort to build a large corpus of collaborative media about neighborhoods in Baltimore--we naturally gravitated to a Creative Commons license--but we couldn't go the final step towards the "gold standard," one that "lets others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon your work." Given the power inequalities and rampant racism of contemporary life in the U.S., it seemed too dangerous--and even unethical--to subject our work with communities in Baltimore to this kind of remix.

Needless to say, like us, other anthropologists have not been especially eager to enjoin remix in their own work, although they've certainly had their own work remixed by others, as when footage from

Adam Fish got remixed for pro-Palestinian hip-hop. Sometimes anthropologists have invited remix, as Chris Kelty did after the open source/ creative commons

Two Bits was published. In good, open-source fashion, the book was "ported" by readers onto different platforms, but that seems to have been the limits to the monograph's "remix"--beyond that of traditional scholarly remix whereby influential texts shape the scholarship that comes after them.

Despite these somewhat tepid engagements with remix, and the ethical responsibilities we owe the communities with whom we work, we believe that remix can offer anthropologists some important possibilities, but not in the ways, perhaps, that Lessig and Jenkins originally envisioned. Instead, we decided to remix ethnographic data about the community with members of the community. To create, in other words, derivative works about our work with our community collaborators in order to better disseminate anthropological media to audiences on a different platform.

From 2013 until now, we've been experimenting with different app platforms, including

ARIS and

MIT App Inventor. These both support geo-located apps, and we've produced some apps about Baltimore. But the big impetus for our app remix has come in the form of a structured, plug-and-play platform for tour apps called "

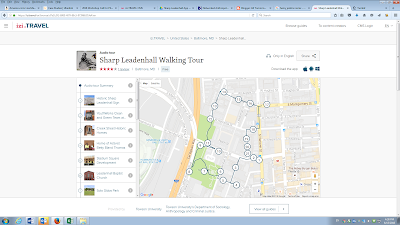

izi.travel". It's readily available on Android or iOS platforms and is free (although not open source). While it lacks the programmable interface of MIT App Inventor, it makes up for it in the capacity to upload multimedia onto the app, including text, video, photograph and audio, all accessible through a geolocated map. With izi.travel, we move from a miscellany of media about a South Baltimore neighborhood to a remixed, multimodal experience that engages app users on multiple cognitive and sensorial levels.

There are several things to keep in mind when making your anthropological media into an app: 1) your media is going to be experienced by people walking around with a smartphone, so it needs to be short and simple: brief interviews, short clips, terse historical notes. 2) Smartphones allow you to use audio as well as visual media--take advantage of this by including some interview material with interlocutors and by turning some of your narrative into an audio tour. 3) Include notes on directions! Even though our app comes with a Google map embedded in the smartphone interface, it's reassuring to have someone tell you to "turn right at the corner"--especially when you're encountering a neighborhood for the first time!

In addition, there are several things are worth pointing out. First, our app is free and the content we've loaded up is under a creative commons license. Second, we produced the app with the same people we've worked with during Anthropology By the Wire--i.e., the derivative remix is also a collaborative work. Third, we agree, as part of our ethical commitment to our interlocutors, to monitor how this multimedia data is utilized. As we say in the our letter of consent (vetted by our institution's IRB):

If you do choose to allow us to place text, audio, photographs and/or film online, then we promise to monitor this content using different tools in order to find out how the material is being received, and how it's being used. Similarly, if you discover that media we've made together is being used in a way you find inappropriate, please contact us immediately. (from Networked Anthropology, p. 128)

The final product is the "

Sharp Leadenhall Walking Tour". What we hope we've produced is something that is anthropologically dense and critical, but that still gives people an opportunity to discover a beautiful neighborhood!