What are faculty thinking about generative AI? In my role at our faculty center, I speak to faculty often on the problems they face teaching in the era of AI, and the workarounds they've come up with. The advent of publicly available generative AI platforms was not something people in my field (anthropology) or other faculty in the social sciences and humanities were clamoring for. And yet here we are. This has led to many responses: anguish, certainly, but also ways of incorporating--or at east channeling--the usage of generative AI in the classroom.

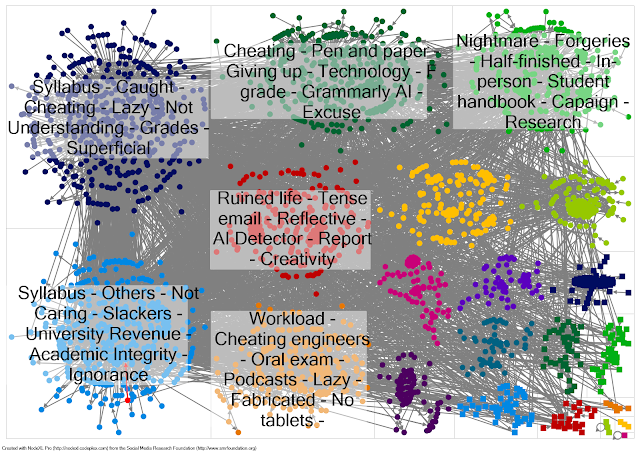

But what about faculty outside of my university? I used NodeXL to download Reddit data from the "/Professors" subreddit using the keyword "AI." This generated records of about 2500 users posting, commenting or replying for a total of 7000 contributions to the debate. I then grouped the data in clusters of similar postings, and abstracted the top words from each group as indicated by "up-vote" (which functions as more of a "like" in Reddit). As you can see, faculty were not particularly optimistic about AI in 2024. Yes, there were a couple of more computopian posters (and at least one computer scientist) who chided the community for rejecting what they saw as inevitable. But most worried that their efforts to teach writing, critical thinking, methodology and analysis were thwarted by student reliance on generative AI. Cynically, they predicted their university's tolerance for AI cheating, and speculated over their ability to continue as faculty under these conditions.

In 2024, Reddit sold their content to Google to train their large language models. This would have been been more objectionable, perhaps, if it wasn't already abundantly clear that generative AI have already been trained on Reddit, which maintains a relatively open API at a time when most social media have monetized their social network data. But what happens to that Reddit data when its re-constituted by generative AI? I decided to prompt Microsoft's Co-Pilot (to which I have enterprise-level access) to generate a spreadsheet of a Reddit conversation on AI between professors. Here's the prompt: "I would like you to generate an excel file similar to a Reddit conversation on a subreddit called "professors." The posts should discuss ChatGPT and student work from the perspective of the professor, and should include comments and replies to those comments. There should be 4 columns in the spreadsheet: A (person commenting or replying); B (person whom A is replying to); C (the text of the comment or reply); and D (the date of the reply or comment). Please populate the spreadsheet with at least 20 comments and 350 replies to those comments."

Co-pilot returned a network with with just 10 users, with 350 edges representing multiple re-postings(?) of user posts. Re-posting really isn't a thing with Reddit, so perhaps there's some confusion here with XTwitter. Since this is a much smaller network, I just labeled the 10 nodes with key words from their posts. The comments are a near "upside down" to the actual Reddit discourse over 2024, generally praising the efficiencies of generative AI and, when critical, speculating over the need for faculty at all (hence the precarity). Of course, there's a snarky comment on "Clippy," the irritating Microsoft assistant. The network itself, while smaller, is also structurally different. The actual Reddit network has a density of .001158737. In network measures of density, "1" would represent 100% connection--everyone connected to everyone else. So .0012 may not seem like much, but it's typical of social media networks where, after all, most of us don't feed the trolls and we save our replies for issues (and users) that we really care about. On the other hand, my AI-generated network has one of 0.966666667--an almost perfectly connected network where everyone has replied to everyone in a style of a polite and ploddingly inclusive panel discussion.

So, I guess that Co-Pilot does a lousy job simulating a subreddit? Yes, but, I think, more than that. It wasn't that long ago (2023) when XTwitter adopted a fee-based model for API access. That decision placed Twitter data beyond the reach of most of us. When social media data disappears behind paywalls, we (ordinary researchers) no longer really have access to the "connected action" of social media. While we can certainly look at social media, this only exposes us to our respective corners of the media platforms we inhabit and the structural components of social media are lost. But what happens when social media content is sold to OpenAI or Google Gemini? When social media disappears into a large language model, both the content and the connections are lost, and the simulated networks produced through generative AI manage to misrepresent social media on both fronts. Since Co-Pilot's inner workings are opaque to us, it is unclear if these results are the result of deliberate choice, unintended bias or something else.