Multimodality describes an anthropology across multiple media platforms--an anthropology that traverses film, photograph, theater, design, podcast, app and game (to name a few) as well as conventional modes of print representation. But multimodality is a restless, protean concept, one that has already exploded its initial demarcation (modes of dissemination) into a spectrum of engagements. Multimodality is about the platforms we use as we produce our work (social media, blogs, websites), and the social media that ripples out from it as people share, comment, re-mix and appropriate. Finally, multimodality is the acknowledgement that people are engaged in anthropologies of their own lives, and that these productions (YouTube videos, Instagram photos) are worthwhile of attention as ethnographically intended media in their own rights. By multimodality, then, we re-cognize anthropology along 2 complementary axes--a horizontal one that links together phases of ethnographic work that are oftentimes held distinct from each other, and a vertical one that links our anthropological work to the anthropologies of our collaborators. Moreover, with the development of new media, new media platforms, and new forms of collaborative work, we would expect these axes to multiply. Ultimately, multimodality takes the arbitrary divisions we make in our work and in our collaborations to task, and offers up new possibilities for old dilemmas.

Many visual anthropologists are, of course, multi-modal avant la lettre: their finished, ethnographic film is preceded by countless edits, photographic stills and recorded interviews. But all of us are multimodal anthropologists; in an age of social media, anthropologists spread ethnographic filaments through multiple platforms before they engage in the "real" writing on their print monographs and journals. At this level, multimodal research means tracing this arc through social media before, during and after ethnographic research.

A short example:

In 2014-2015, I was doing research in Seoul on representations of the city through both mass media (novels, film, web comics) and through social media, particularly social media produced by neighborhood groups affiliated with various "village media" (마을 미디어) projects. In particular, I was attracted to social media postings of alleyways and narrow roads, photos that looked like they were from the 1970s but were actually contemporary photos of the few remaining places in Seoul where you can see the old-style neighborhoods. Decades of hell-bent urban development had developed (and re-developed) Seoul's neighborhoods beyond recognition, and narrow roads crowded with old-style homes (도시 한옥) were now a thing of the past--with the exception of specially designated tourist neighborhoods like Seoul's Bukcheon.

What was left was a sense of loss and nostalgia, and rather than the "poverty porn" of similar photographs in the U.S. (and in my own city of Baltimore), these social media postings vacillated between sentimental longing for a time before Korea's "Apartment Republic," when crowded streets and narrow, connected homes meant that people knew each other in multifaceted, intimate ways, on the one hand, and the commodification of that nostalgia for capital gain, on the other. Extremely popular programs like "Reply 1988" (응답하라 1988) were on television, steeped in nostalgia for the previous times. It is no mistake that this television drama ends with the complete destruction of the neighborhood under a redevelopment scheme--this was the experience of an entire generation of people (the 386 generation) who came of age in the 1980s.

(Final scenes of the old neighborhood in Reply 1988 (2015))

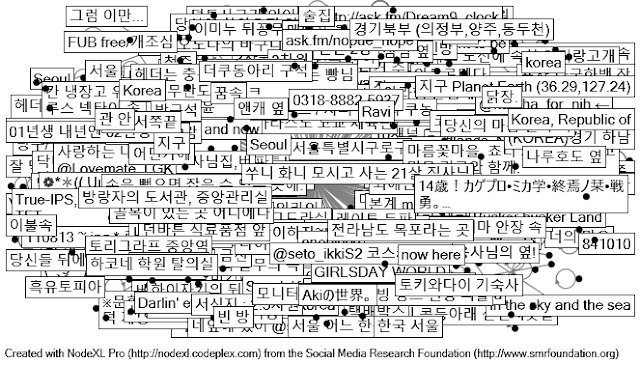

Similarly, Facebook and Twitter were filled with photographs and remembrances of vanishing neighborhoods, and I began to follow certain account and Facebook groups that were particularly rich sources of postings and re-postings of images of alleyways. The first diagram shows tweets containing the keyword "alleyway" (골목길), ranging from "singleton" posts and photographs to others that were re-tweeted many times. Photos from Ehwahdong (이화동), Bukcheongmaul (북정마을) and other neighborhoods were re-tweeted multiple times.

On the other hand, people posting these photos located themselves in various ways that suggested a very cursory--or even incidental----identification with these neighborhoods and with place in general. The diagram below labels people's tweets about Seoul alleyways by the locations they've set in their profiles.

While some locations (e.g., "In an alleyway") suggest a slightly cheeky identification with these places, others ("the world," "In bed") suggest a more alienated, fragmented relationship to life and sociality in Seoul.

I started to collect and archive these diverse media on "Storify", an SNS platform that allows you to aggregate and comment upon other SNS content. Storify enabled me to keep a notebook in a digital age when the ephemerally of content could easily mean that a post to Instagram today may be very difficult to find again tomorrow.

I started to collect and archive these diverse media on "Storify", an SNS platform that allows you to aggregate and comment upon other SNS content. Storify enabled me to keep a notebook in a digital age when the ephemerally of content could easily mean that a post to Instagram today may be very difficult to find again tomorrow.

(a screenshot of a Storify collection of social media posts about Seoul's "Jangsu Village".)

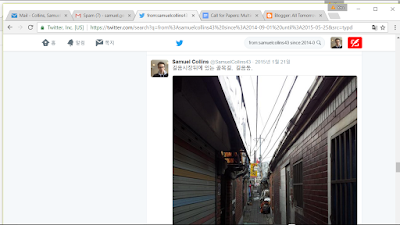

Finally, I began to take pictures of Seoul alleyways, starting with one from my old neighborhood in Gileumdong, and then posting them on Twitter. Concerned with issues of privacy, I was careful to avoid photos of people and personal effects. I confined myself to public streets that, while reflective of Seoul’s older development, did not suggest poverty.

These images were re-tweeted and “liked” a few times, and

were finally posted to a Facebook fan group collecting images of Korean

alleyways. The graph below shows users

posting to the Facebook group, with their names replaced by the numbers of “likes”

for each post. The posts led to some

online interviews about Seoul’s spaces and photography, but, by summer of 2015,

much of this particular arc of photographic circulation had ceased.

Conclusions

This is not visual anthropology. And nor is this “ethnographic”

in any complete sense—it’s a fragment of ethnographic work refracted onto

different media, different digital platforms.

A key component of this multimodality is its social dimension. This isn’t just me posting some mediocre

photos of empty streets; my engagement with these media brings along the

engagements of hundreds of other users together with the circulations of their

media. We’re linked—networked—in a way

that undermines the pretensions of ethnographic author-ship (and

authority). With multimodality, we may not always get to say what we mean--or, rather, "saying" and "meaning" are the aggregate decisions of multiple nodes. Multimodality pulls our work into different

productions, different circulations and, ultimately, different meanings. We can utilize various analytics to trace these differentiated contexts, but we must endeavor to do so in order to not

just examine the way the significance of our ethnographic changes according to

each configuration, but to also trace the socialities each platforms engenders.

An Invitation

If you are also working along multimodal lines in your research, please consider submitting something to us in the "Multimodal Anthropologies" section of American Anthropologist.

We are accepting essays (print and photo), review essays and reviews that explore the contours of multimodality for possible publication in American Anthropologist. To submit a manuscript, or for more information, please contact us:

Harjant Gill (hgill@towson.edu)

Matthew Durington (mdurington@towson.edu)

Samuel Collins (scollins@towson.edu)

@Dept. of Sociology and Anthropology

Towson University

8000 York Rd.

Towson, MD 21252

USA